Joshua travels to Iraq: unconventional reflections on Iraqi heritage & tourism

written by: @jpwoop

Joshua from Australia (originally from Hong Kong) travels to Iraq and reflects on Iraqi culture, history and his stay in Uruk, Chibayish, Hillah, Najaf and Mosul.

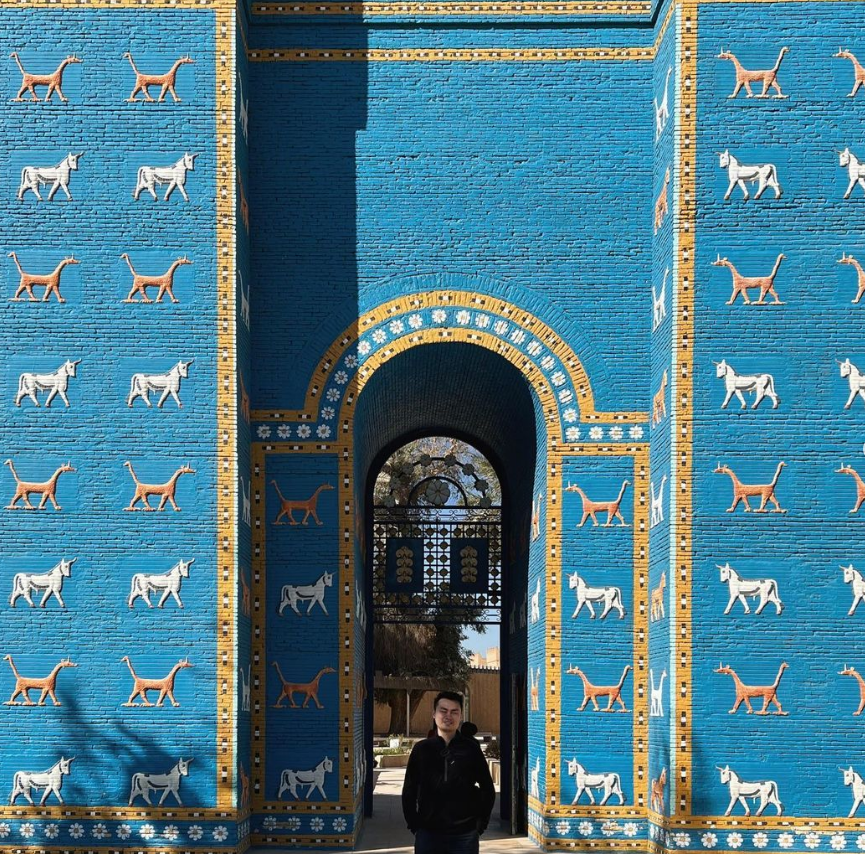

Iraqi archeology in Uruk and Babylon

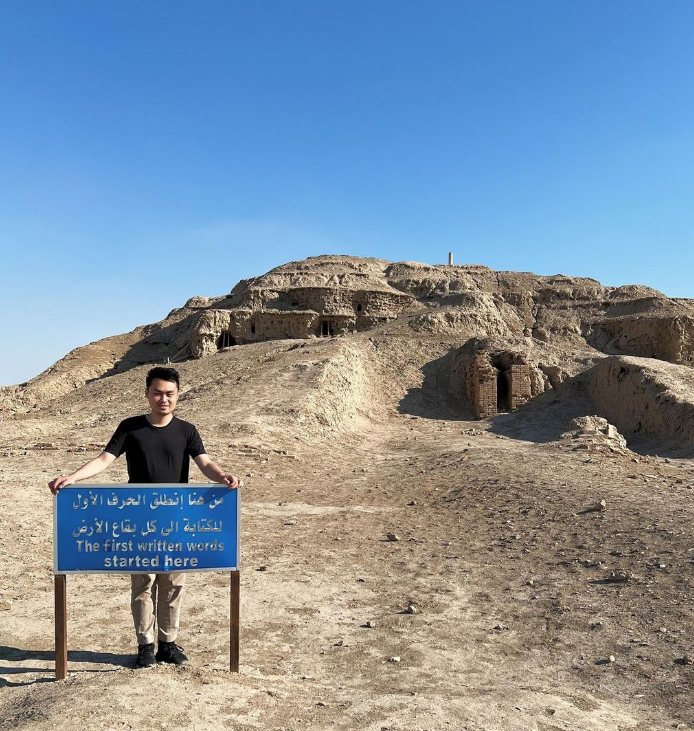

One may easily be misled by the many photos of travel influencers in front of the “The first written words started here” sign into thinking that Uruk is just a photo stop.

But in reality photos cannot really capture the scale and historical richness of the site of Uruk, the ancient Sumerian city founded in the 4th millennium BC.

It is particularly sobering to see the tools left on site by archeologists from decades ago, realising that there is still so much history buried deep underground. The idea that the boundaries of humanity’s self-knowledge is defined by how much funding and attention archeological projects receive is honestly quite depressing. Not least when the wealthy seem to be deeply interested in colonising other planets, where Jeff B unironically thanked his workers for getting him into space.

Pillage, theft, “sharing arrangement” or whatever you call it, they are in effect the same thing: historically significant artefacts being taken away from their countries of origin and locked away in western museums, inaccessible to the vast majority of people with a weak passport.

One can find Mesopotamian tablets even in the smallest Western university museums like that of the University of Sydney. I think one can legitimately question the utility of placing these artefacts in locations where vast majority of its visitors do not have the interest or context to understand them.

Trauma tourism in Mosul

A number of western/foreign YouTubers have taken the predictable path of creating self-indulgent “video tours” of the ruins of old Mosul, with highly sensationalised titles like “ground zero of Daesh massacre” (translated from a video in Chinese). One cannot help but feel deeply uneasy about this. The idea that these videos are – as they appear to claim – a way to “raise awareness” or “bear witness” is hardly persuasive. It seems obvious that one does not need to watch a YouTube video to appreciate the horrors of war. Nor are foreigners who had only spent a day or two in a city well-placed to speak for the locals. Even for videos that paint a purely positive image – they remain contrived and patronising.

I owe a great deal of my thinking to the careful observations by @lostwithpurpose and a few other ethical travel bloggers on the harmful (colonial) practices of western travel influencers. The harms of “trauma tourism” are particularly important to acknowledge in this context. This is why I had no plan to visit Mosul until a friend said it is historically too important to miss. And now after my visit I am still convinced that these stories should be told by those who lived through it (such as by the wonderful Bytna centre on Mosuli cultural heritage @bytna.mosul), not by selfish influencers who are desperate for clout.

For these reasons, I’ve decided not to include photos of the ruins of old Mosul.

An unconventional (and probably incomprehensible) reflection after my trip to the Iraqi Marshes

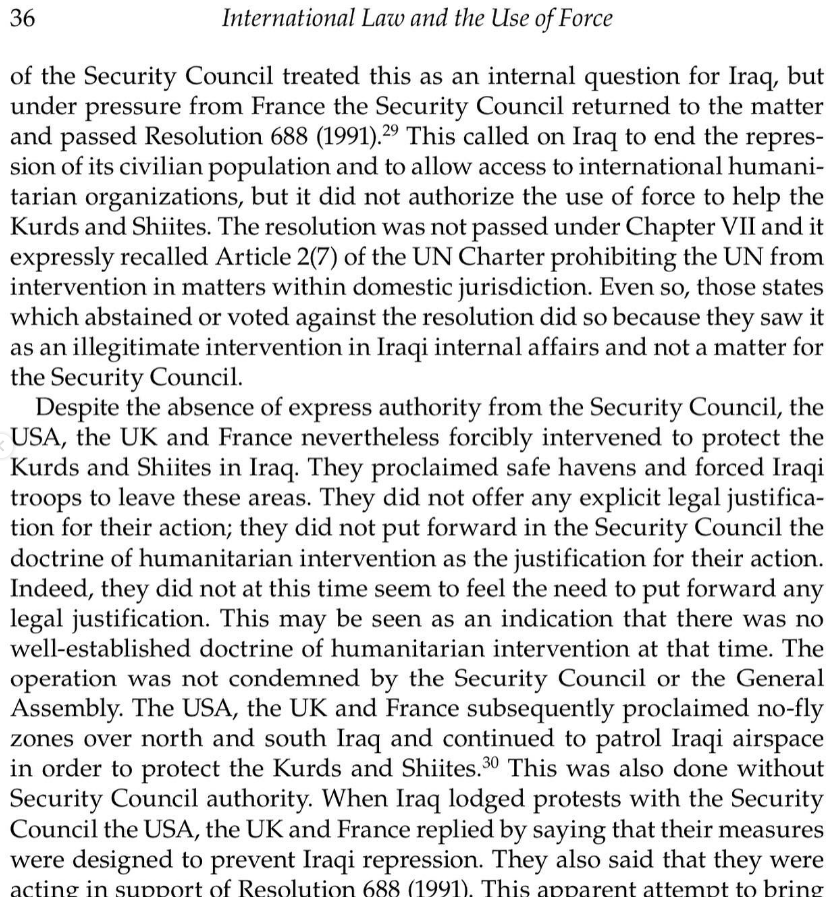

Christine Gray’s text on the use of force was one of the mandatory readings in a public international law class I took a couple of years ago. I remember reading about the Shiite Arabs of South Iraq when studying the topic of what they call “humanitarian intervention”. Everyone who has studied the topic knows how to regurgitate the legal significance of Uganda, East Pakistan, Iraq, Kosovo, etc, and knows that it is academic expectation to repeat the imperialist garbage about “illegal but legitimate” interventions. Of course it goes without saying that “humanitarianism” is generally a disguise for military and other motivations — But what really strikes me now is how despite having written essays and exams on the “legality” of humanitarian interventions, I know very little about the events that happened in each of these countries.

Hearing about the draining of the Iraqi marshes has prompted me to revisit the relevant sections in Gray’s text. It made me think about those bona fide international lawyers who are genuinely committed to building a “rule-based international order”. Gray’s text is where they turn to when they need guidance. For me, the extract of the text shows the kind of sanitised, clinical narrative that lawyers work with. The description of humanitarian tragedy is decontextualised and *dehumanised* by design. The “sources of law”, “state practice”, “opinio juris” etc require a lawyer to look at UN resolutions, and what the Western powers have said or done. Ironically, the humanitarian subject of these legal analyses on “humanitarian interventions” are completely erased.

I think the lesson to be drawn from a visit to the Iraqi Marshes is a simple one: listen to people’s stories in their own terms.

The birth celebration of Imam Ali in Najaf and Kufa

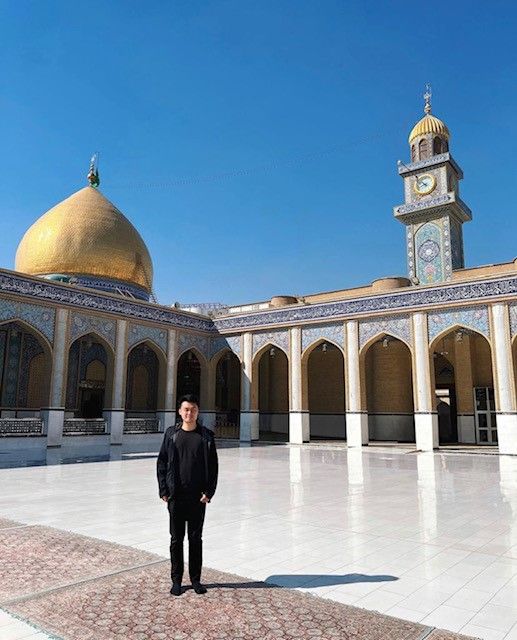

Growing up in a sterile, middle class Protestant church in Hong Kong that looks like an office (fits the soulless capitalist aesthetics perfectly), where the Sunday routine was a heavily scripted song-sermon-song “program” that brought everyone to sleep – visiting the shrines and mosques such as those in Karbala, Najaf and Kufa is a completely different (and revelatory) experience. Beyond the grandiose interiors, what is most striking to me is the people. I don’t have the words to describe the surreal experience of visiting the Imam Ali shrine in Najaf the evening before his birthday. The celebratory chanting was intense, out-worldly, if not overwhelming. It was a kind of raw energy that I’ve never experienced in my life.

I think I get a better sense of what my friend Ali meant when he said that Islam is not so much about rules, as it is about the spiritual experience and the stories. As an outsider, while I may not understand the significance of these stories, to witness the way others are being inspired by these stories is a remarkable experience.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of IraqNow.

Contact us if you want to share reflections or pictures on your trip to Iraq. Read part 1 and part 2 of the Iraq traveling series on our website.