A brief history of Sinjar: understanding the historical roots of the 2014 Yazidi genocide.

The Yazidi genocide: a hundred years in the making.

By Amir Taha

Many explanations of the 2014 Yazidi genocide rely on short term causes such as the rise of ISIS, Kurdish disarmament of the Yazidis and the recent history of the 2003 US occupation. These causes do play a very important role in the Yazidi genocide, but if one takes a long term perspective on the Sinjar district it's striking to see that this massacre was over a hundred years in the making. Within a span of only one hundred years the Yazdis of Sinjar went from a highly independent and tolerant rural community to one victimized by ISIS and made reliant on vulnerable Iraqi state institutions. Genocides do not happen in one day; they follow a long historical trajectory of discrimination, social wreckage, dispossession and finally elimination. In this article I shed light on this trajectory and give context to ongoing political contentions in Sinjar but also to the root causes that allowed this genocide to happen.

The origins of Yazidis in Sinjar

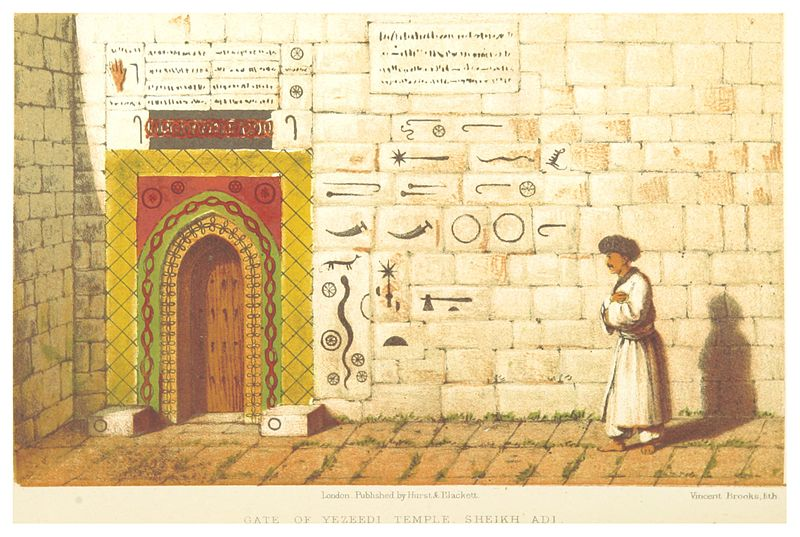

Sinjar is home to the oldest Yazidi communities of Iraq. The history of the Yazidi religion in Sinjar goes back centuries even before the rise of Islam in the region. Yazidism however flourished in the 12th century. This revival was sparked by Sheikh Adi’s return to Lalash (located in the Shaykhan district, Iraq). Through Sheikh Adi's mystic insights, a new understanding was formulated about the Divine. For the tribes roaming Northern Iraq at the time Yazidism was attractive because the religion had a certain flexibility to it better suited for a nomadic tribal existence than the other more strongly institutionalized religions. It can however not be denied that the Yazidi belief system developed in interaction with traditions of Islam, Christianity and Zoroastrianism but maintained its own beliefs and rituals within this context (Fuccaro, 1999).

During the 20th century different political movements tried to bring the Yazidi community on their side by making claims about their beliefs that fit the ideology of the movement. When that failed a more violent approach was employed. The Arab nationalists claimed for example that Sheikh Adi was an Arab and that the Yazidis are allies of Arab nationalism. The Kurdish nationalist movement claimed that the Yazidis were originally Zoroastrians, a religion many Kurds in the past professed, and therefore Yazidis are Kurds foremost. In reality, Yazidi relations with Muslim Kurds and tribes was always tense. The Yazidis therefore tended to remain suspicious of both nationalist movements. A strand within the Yazidi community preferred to stay independent of all. This ambiguity regarding who they Yazidis were and where their loyalty lies made social movements and states anxious to categorize them in a way that benefits their own political narrative (Savelsberg et al., 2010).

Sinjar, Yazidi tribal leadership and tolerance

Sinjar is a district and a town in the Nineveh plain where a manifold of communities and religions come together. Sinjar is mostly populated by Iraqi Yazidis but has also been home to a diverse group of Shias, Sunni, Christian and Jewish Iraqis. In Iraq live around 550.000 Yazidis. Mount Sinjar was a haven for nomadic Yazidi Tribal confederations who settled there after a wave of Ottoman persecutions in the 15th century. Different Yazidi princedoms came and went in Sinjar as the Yazidi community tried to survive in an environment considered as a strategic zone for the Kurdish tribes, the Ottoman empire and the Persian Safavid empire.

Around the year 1900 the Yazidis in the Sinjar region settled as farmers with a strong tribal identity. This strong tribal identity was the opposite of the Yazidis of Shaykhan who were slightly more urbanized and strongly tied to Yazidi religious institutions. The shrines, the religious priests and the believers all were however part of a tightly knit religious network. Some scholars however claimed that some priests exploited the peasants of Shaykhan. This was more the case in Shaykhan than in Sinjar where the power of the priests was weaker and that of tribal heads stronger. Because tribal heads had more power than religious authorities, Sinjari Yazidis had a different self-identity than the Yazidis of Shakhyan. Since tribalism was much more important in Sinjar than religious rigidity, it was common to see a diverse composition of tribes with Christians and Shi’a Muslims with a Yazidi tribal head. A certain tolerance upheld between the different ethnic and religious groups of Sinjar under Yazdi tribal leadership. The Tribal leaders of Sinjar were widely respected for both their holy lineages and charisma.

Important to note is that the Yazidi priests also functioned as intermediaries with outside powers such as the encroaching British empire or the expanding postcolonial Iraqi state, for the local community. The continuous authority of religious leaders also supplied a sense of continuity within the Yazidi community. For the British apparatus and the Iraqi state the Yazidi’s independent financial revenues, social cohesion and religious authority posed a threat especially to the British empire. The British had an interest to install a pro-British state in Iraq when they colonized it but also wanted to squash local community independence and institutions that could threaten British dominance (Ali, 2019).

The rebellious Yazidis and the British empire.

A recurring problem between the Yazidis and the British, Iraqi or Ottoman state since the 1880s was trying to force the Yazidis of Sinjar to conscript in the army. The Yazidis already felt alienated by either the Ottoman's increased Turkish nationalism or a renewed assertiveness that saw the Yazidi elite both as a suspicious subversive group that was Kurdish and non-Muslim. The British mostly felt threatened by the self-sufficiency and independence of the Yazidi communities, especially in Sinjar. Tribal mobilization and insurgency by the Yazidis of Sinjar was recurring and limited the success of both the British and the Ottomans in defeating the Sinjaris and forcing them to conscript. The Yazidis of Sinjar were very aware of the fact that conscription would wreck tribal loyalties, economic sustenance, and political power to keep independence. The first uprising against the British in 1925 ended in a murderous mass bombing campaign against Sinjar by the British air force. One of the larger and more famous acts of resistance was the large 1935 Yazidi uprising against the British backed Iraqi monarchy.

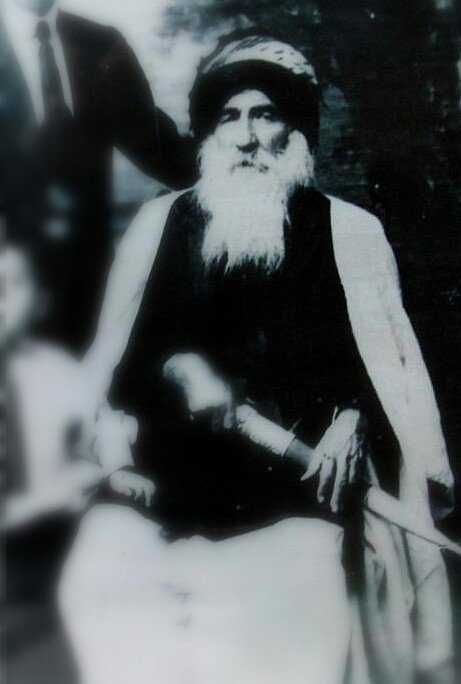

In June 1935 Sheikh Khudaida, son of Hamu received a letter from the governor of Mosul that his underlings must conscript into the Iraqi army. The Sheikh refused and other tribesmen began to sell their belongings so that they had money to buy arms in case they had to defend the refusal to conscript. Under the impression that it was now a hostile situation, Yazidi tribesmen attacked government functionaries. When the recruiting officers arrived in October the revolt under the leadership of Dawud al Dawud started. The Iraqi monarchy mobilized the army to quell down the revolt. The year 1935 was a busy one for the Iraqi army as tribal revolts in the south were ongoing as well, the monarchy had a challenging time enforcing its legitimacy among the Iraqi people. The squashing of the Yazidi revolt killed over two hundred people and jailed over 350 of them. The whole operation was a failure for the Iraqi government, they only got seventy recruits out of Sinjar and only 4 of those were Yazidis. It was clear that to gain control over the Sinjar a way must be found to limit their economic and social independence first (Fuccaro, 1997).

Republican Iraq: urbanizing and Arabizing

When Iraq became a republic (1958) and the Kurdish nationalist movement (KDP) fell into conflict with the central government, the KDP attempted to exert influence on the Yazidi community to join them against the Iraqi state. The KDP tried to recruit Yazidis to their cause based on the idea that they saw the Yazidis as part of the Kurdish nation. However, historically speaking the relations between Yazidi and non-Yazidi Kurdish tribes were not always peaceful, there was a reluctance to join the KDP in Sinjar. However, since Sinjar was a ‘’disputed’’ area it threw the Yazidis right in the middle of the conflict between the Iraqi government and the Kurdish movement. Yazidis had no choice but to fight on the side of KDP. The KDP also forced the Yazidis and other minorities in this area to either fight for them or else their weapons would be taken away, a familiar tactic, risking vulnerability and death. The ambition to integrate Sinjar into an autonomous Kurdish region was part of Barzani’s strategy. This was an experience that still affects the Yazidi community of Sinjar's relation with the Kurdish authorities today.

Under the Baath government (1968-2003) the conflict between the KDP and the Iraqi government was temporarily concluded in 1975. The Baath regime however still felt that the isolated Yazidis of Sinjar were a serious threat if they remained tribal, unsettled and rural. The Baath party therefore began a forced urbanization and Arabization campaign. The Baath government confiscated Yazidi settlements, homes and land and destroyed it all. The government then forced Sinjar’s inhabitants to move to ‘’state’’ villages. Part of the population were forced to live in places far and distant from Sinjar even. The Kurdish language was made forbidden and many were forced to register as Arabs in these new collective villages. The Baath also settled Arabs in Sinjar. Till this day one important and significant aspect to the Yazidis in Sinjar is that Arabic is a much more common language than Kurdish because of this. This has also to do with the fact that Sinjar remained under Iraqi control even after the Kurdish Regional government (KRG) was temporarily severed from Iraq during the 1990s sanctions (Ali, 2019; Savelsberg et al., 2010).

Kurdification of Sinjar and the Yazidi genocide

Ironically after the fall of the Baath government in 2003 the Kurdish Regeional Government implemented a “Kurdification’’ campaign in Sinjar almost in similar style to the Arabization campaign of the Baath government. The KDP powerfully asserted its dominance by intimidating Sinjari people for showing interest in staying tied to the Iraqi state and joining rivaling parties. Mustafa Barzanis’ KDP also made sure to have all the administrative positions of Sinjar in his own hands and made sure that local mayors were not locally elected (“The KRG’s Relationship with the Yazidi Minority and the Future of the Yazidis in Shingal (Sinjar),” 2017).

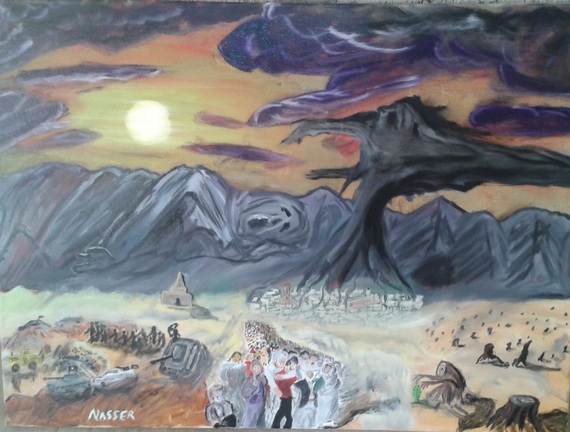

Despite all these Kurdish investments in Sinjar it remains one of the most underdeveloped districts of Iraq. The people and the Yazidis of Sinjar therefore resented the presence of the Peshmerga and the KDP in their district. The fact that the KRG did not protect them when ISIS attacked in August 2014 severed any potential trust in the Yazidis had in the Kurdish authorities. The people of Sinjar were aware of the coming attack of ISIS two months prior and therefore requested several times that they had to be protected because an attack from ISIS was only a matter of time. The KRG however refused to act. It is estimated that ISIS murdered five thousand Yazidis. The victimization of Yazidis by the KRG however continued after the liberation of some parts of Sinjar from ISIS. The KRG placed an economic blockade on the Yazidis who returned to Sinjar by actively starving them by denying them access to basic goods like rice and fuel. As ISIS was on the verge of defeat in 2017, the popular mobilization forces helped liberate Sinjar together with the PKK forces. Once the PMF settled itself it helped to create Yazidi units to take care of their own security (“Kurdish Blockade of Sinjar Harms Yazidis”, Syria comment, 2016).

Today Sinjar remains a point of contention between the Iraqi government, the Kurdish authorities and the Popular Mobilization Forces. The persistent attempts to conscript the Yazidis, destroy their villages, and settle them in ways to break their social and economic independence the past hundred years was central as to why the Yazidis of Sinjar were massacred once ISIS came along. As the Iraqi government decided to fully hand control over Sinjar to the KRG, the people of Sinjar understood that this was an attempt to subject them once again to outsiders who have a political agenda intended to exploit them (Protests in Iraq over Control of Yazidi Region, Daily star, 2020).

Amir Taha is a historian at the University of Amsterdam focusing on political mobilization during the modern history of Iraq.

Sources:

Ali, M. H. (2019). Aspirations for ethnonationalist identities among religious minorities in Iraq: The case of Yazidi identity in the period of Kurdish and Arab nationalism, 1963–2003. Nationalities Papers, 47(6), 953–967.

Fuccaro, N. (1997). Ethnicity, state formation, and conscription in postcolonial Iraq: The case of the Yazidi Kurds of Jabal Sinjar. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 29(4), 559–580.

Fuccaro, N. (1999). The Other Kurds: Yazidis in Colonial Iraq. London: IB Tauris.

Kurdish Blockade of Sinjar Harms Yazidis: New HRW Report. (2016, December 7). Syria Comment. https://www.joshualandis.com/blog/kurdish-blockade-sinjar-harms-yazidis-new-hrw-report/

Protests in Iraq over control of Yazidi region. (2020, October 12). Morning Star. https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/w/protests-in-iraq-over-control-of-yazidi-region

Savelsberg, E., Hajo, S., & Dulz, I. (2010). Effectively Urbanized. Yezidis in the Collective Towns of Sheikhan and Sinjar. Études Rurales, 186, 101–116.

The KRG’s Relationship with the Yazidi Minority and the Future of the Yazidis in Shingal (Sinjar). (2017, January 31). Syria Comment. https://www.joshualandis.com/blog/krgs-relationship-yazidi-minority-future-yazidis-shingal-sinjar/